Grosseto

The emperor and the prince, noble birds of prey and steeds

Frederick II of Hohenstaufen, the “Arte venandi cum avibus” and the high flight of Maremma’s “noblemen of the sky” - by Ambra Famiani

The emperor and the prince, noble birds of prey and steeds

Frederick II of Hohenstaufen, the “Arte venandi cum avibus” and the high flight of Maremma’s “noblemen of the sky” - by Ambra Famiani

Stupor mundi in medieval Grosseto

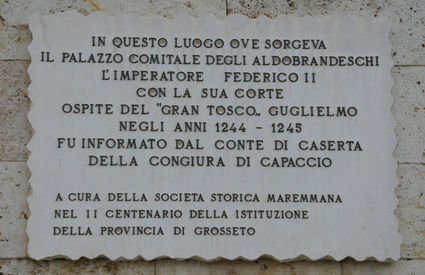

A plaque in the noble palace of the Aldobrandeschi commemorates the time when Frederick II of Swabia, Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, stayed in the civitas as a guest of the Gran Tosco Guglielmo. Over the course of his sojourn in the structure, the emperor drafted his novellae, a collection of regulations aimed at reforming the Constitutions of Melfi; maintained a normal diet; appointed his son Frederick of Antioch to Sacri Imperi in Tuscia et per totam Marittimam vicarious generali; meanwhile the officials of his itinerant court issued privileges and mandates.

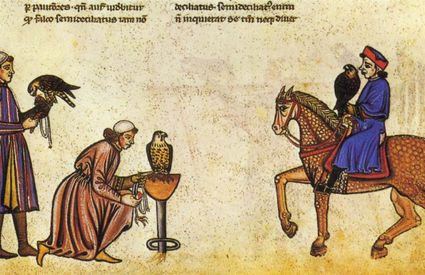

And it was perhaps right here where he made use of the forests, the swamps and the coastal ponds in his hunting and animal observation activities. He curiously observed both water and land critters, but was particularly interested in birds of prey, illustrating their specific characteristics for their use in falconry. More specifically, he worked to teach and train these birds so he could use them for his own hunting purposes, which was the topic of De arte venandi cum avibus, the precious manuscript he compiled prior to 1249.

In practicing this art, the emperor grew the population and selected horses well-suited for hunting that were not afraid of falcons. This was an important sort of behavioral characteristic that was transmitted through the centuries to the Persano horse breed.

A knight, a passion and a valiant horse, symbolizing gallantry

And here’s where the thin thread of the past weaves together with that of the present.

During the pickup service for the Centro Raccolta Quadrupedi of Grosseto (a collection center), Alduino da Ventimiglia di Monforte Lascaris stumbled on something. A descendant of Frederick II, the prince hailing from Sicily who has had falconry in his blood for more than a thousand years, Alduino discovered that the last superior Bourbon horses, the Persano, heirs of a glorious history, had been confined here for government purposes.

He then began a personal mission of saving them, coming into the possession of the last few purebred ones, and managing to save the race from extinction. He dedicated his life to these extraordinary animals and today owns around 70 of them.

The falconry prince and the sacred birds of prey

A love coming from far away, his first horse was a Persano, the breed that the noble knight raised in the Castello di Luriano in the upper Maremma, where he moved years ago and where he also raises birds of prey and goes hunting with a holy falcon, just like they did in medieval times.

Proud and even haughty in their perches, their hooked beaks, their sharp claws, their beautiful streaked and bright coloration, the hawks, gerfalcons, eagles and royal owls live here in the aviaries near the stalls, as Alduino’s beloved and respected comrades of Alduino.

A protector of centuries-old practices, a connoisseur of horses and a falconry expert, and the guardian of Frederickian ars venandi, he founded the Accademia Italiana Cavalieri di Alto Volo (roughly translated as the Italian Academy of Knights of High Flight), in a move rather befitting of his legacy with the Stupor Mundi:

For the man who wants to rediscover himself, to do a bit of soul searching, this means continuing along the same ethical lines and conceiving of a world in which man is not separate from nature, but part of it. Birds of prey help us not to think of the land, but to think from on high. Because they are the noblemen of the sky.